Introduction

Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has emerged as an increasingly safe and effective therapeutic procedure, with origins tracing back to the early 1960s.

Today, HSCT is a crucial curative strategy for patients with haematological malignancies, such as leukaemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma, myelodysplastic syndrome, myeloproliferative neoplasm, and for some non-malignant blood disorders such as acquired bone marrow failure syndrome.

Summary of Indications for Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

- Acute myeloid leukaemia

- Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

- Chronic myeloid leukaemia in blast crisis

- Primary myelofibrosis with intermediate or high DIPSS score

- Myelodysplastic syndrome with excess blasts, high-risk multilineage dysplasia

- Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with high-risk disease, Richter’s transformation

- Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- Multiple myeloma & primary amyloidosis

- Very severe aplastic anaemia

Types of HSCT

- Autologous HSCT (patient’s own stem cells)

- Allogeneic HSCT (stem cells from a donor)

– HLA-matched related donor (sibling)

– HLA-matched unrelated donor (local or overseas)

– HLA-mismatched related donor

– HLA-mismatched unrelated donor

– Syngeneic transplant (identical twin, non-identical twin)

– Haplo-identical donor (half HLA-matched, parents or children)

– Umbilical cord blood

Peripheral Blood Stem Cell (PBSC) Apheresis

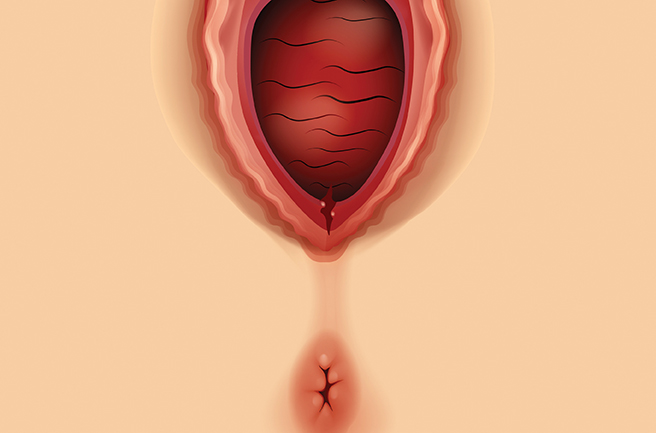

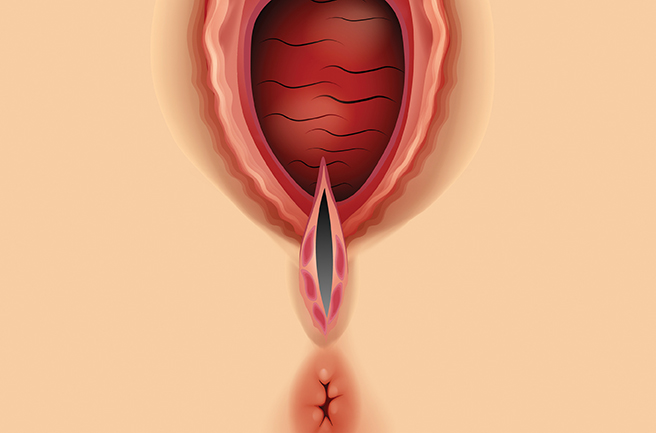

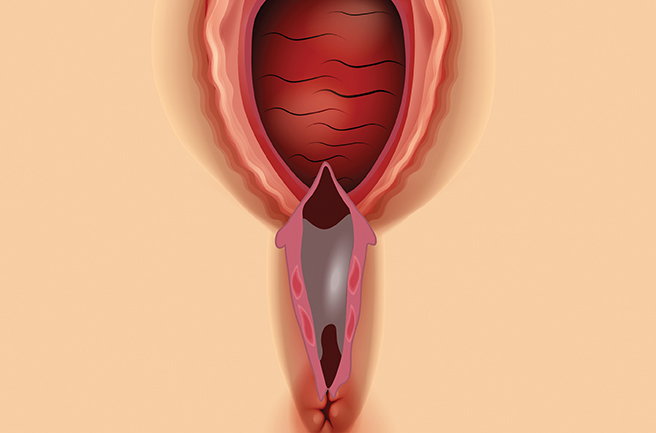

Stem cell apheresis is a unique procedure that collects stem cells from peripheral blood using a cell separator called an apheresis machine. The process begins with mobilising haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) from the bone marrow into the bloodstream, typically through a growth factor called granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). Once enough stem cells circulate in the blood, they are collected through the apheresis machine.

Stem cells are transferred to a collection bag, while the remaining blood components are returned to the body through a catheter. Each session typically lasts 4 to 8 hours, and the procedure may be performed over one to two days, depending on the amount of stem cells required. This non-surgical procedure is generally well-tolerated by both patients and donors.

Basic Principles of Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

Before the infusion of HSCs, patients receive a combination of drugs with or without total body irradiation (TBI) as a conditioning regimen. Conditioning eradicates residual disease, creates “empty space” within the bone marrow cavity, and suppresses the immune system. Following the conditioning, HSCs are infused into the patient, migrating to the bone marrow to produce new blood cells. HSCs can regenerate blood components and reconstitute the immune system of patients whose bone marrow has been compromised due to disease or high-dose chemotherapy. Successful integration of transplanted cells is monitored, leading to the recovery of haematopoiesis and healthy bone marrow function.

Advantages and Risks of PBSC HSCT

Compared to traditional bone marrow transplantation (BMT), PBSC HSCT offers faster blood cell count recovery and a lower incidence of complications. Studies indicate that patients undergoing PBSC HSCT experience quicker haematopoietic recovery, resulting in shorter hospital stays. Additionally, PBSC use has become more common due to its availability and the relative ease of collection compared to bone marrow.

Despite its benefits, PBSC HSCT carries risks. Patients may encounter complications such as infections and organ dysfunction, particularly in the early post-transplant period. One significant complication of allogeneic HSCT is graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), where the donor’s immune cells (the graft) attack the recipient’s tissues, recognising them as foreign. Infections are another primary cause of morbidity and mortality, as the conditioning regimen and procedure significantly weaken the patient’s immune system, increasing susceptibility to bacterial, fungal, and viral infections. Managing these risks requires vigilance, effective prophylaxis, and timely treatment.

Conclusion

While HSCT can be a life-saving treatment, it also entails substantial risks, particularly with infection and graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic transplants. Careful patient selection, optimised conditioning protocols, effective anti-GVHD strategies, and robust anti-infective measures are critical for improving outcomes. Through these advancements, HSCT continues to offer hope for patients with otherwise incurable blood disorders, providing the potential for long-term remission and enhanced quality of life.

All images courtesy of LohGuanLye Specialists Centre

Dr. Teoh Ching Soon

Consultant Clinical Haematologist & Physician

MD (UPM), MRCP (UK), Fellowship in Clinical Haematology (Malaysia), Fellowship in Bone Marrow & Stem Cell Transplantation (Taiwan)

Dr. Teoh Ching Soon is the Clinical Haematologist & Physician in LohGuanLye Specialists Centre. He has a keen interest in the management of malignant haematological disorders such as leukaemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma, myelodysplastic syndrome and myeloproliferative neoplasm. His clinical work also focuses on benign haematological diseases, red cell and platelet disorders, coagulation and haemostasis, consultative haematology and haematopoeitic stem cell transplantation.